Evidence in the NT for the Trinity:

My Conclusions

Now that we have seen the various weaknesses in our review of the presentation of Anthony Buzzard, it is time to draw some conclusions about the doctrine of the trinity in primitive Christianity.

Before doing so, I would like to first affirm my personal belief in orthodoxy. I continue to believe in the trinity, although I cannot explain it. I believe in the dual natures of Christ (fully God and fully Man), although I freely admit the difficulties of holding this position. I base my personal positions on my reading of the NT and on the canons of the various Church councils. I do not agree with those who claim the councils were dictated by politics more than the biblical text. Those who make this claim clearly are not familiar enough with the church fathers of the second and third century. The leaders of the councils (even the Reformers) based their opinions on the NT texts and the writings of these early fathers. The fact is: the NT documents are not crystal clear - if it was obvious we would not have had so much disagreement throughout church history!

- NT Evidence of the Trinity

- The Trinity in the Third Century

- Book Review: On Buzzard and the Trinity

- PDF of the Buzzard Review

I will also admit that the creeds are difficult to defend. The early creeds were drafted to combat particular problems - unfortunately the creeds raised (or created) new issues with each draft.

It is apparent to anyone reading Athanasius's diatribes against the Arians that what is at stake is not which texts from Scripture are used, but the way in which they are used....The lesson for our purposes is that proof texting is not enough... there is some doubt as to whether Scripture supports the creedal confession directly or without great labor. (emphasis added, p.39)

Colin Gunton, "And in One Lord, Jesus Christ...Begotton, Not Made," in Nicene Christianity, The Future for a New Ecumenism, ed. Christopher R. Seitz (Grand Rapids: Brazos Press, 2001), pp.35-48.

Unfortunately, the uncertainty appears to affirm Buzzard's position that the creeds are not based on the biblical text, but on Platonic ideas that had infiltrated the Church. As stated earlier, the creeds are based on the biblical text AND the writings of the second century fathers. But my point here is more to the first part of Gunton's statement above, what is at issue (and has been the focus of my critique against Buzzard) is not the specific proof text as much as how the text is being used. Because Buzzard is a fundamentalist, he is bound to a narrow understanding of the biblical text, and inspiration, which leads to straining of the text(s). Buzzard does this, some of my fundamentalist colleagues do this, and many of the early fathers did this. Literalists cannot easily accept paradox and, as Gunton concludes (referencing Kierkegaard) nothing important can be said without paradox. (ibid., 47-48)

After looking at these particular texts and issues, it is time to put forth an alternative explanation of the trinity in the NT. Buzzard says (p.168) that the synoptic gospels are silent when it comes to the preexistence (and divinity) of Christ and much of his theory is based on the assumption that John's gospel must be in harmony with the synoptic gospels. Yet there certainly is a distinct difference between the representation we get of Jesus in the synoptics and what we see in John's gospel. Even the early fathers saw this, referring to John's gospel as the "spiritual" one.

The belief that all biblical text is basically in harmony represents a conservative view, one that emphasizes the hand of God on the text. This view is fairly consistent with the "inerrancy" position held by many conservative evangelicals. Volumes have been written on this subject so my simplistic statements will not suffice for those who need further explanation (You can read my position on inerrancy).

We will proceed in this theory with the assumption that Jesus is eternal; that He existed with the Father from eternity. The Council of Chalcedon affirms that two natures resided in Christ, "without confusion, without change, without division." Putting aside the difficulties of this affirmation for the time, part of this creed is the humanity of Jesus. If we accept the full humanity of Jesus as presented in Philippians 2, then we can say that Jesus did not have full knowledge - he would not fully know His eternal nature. Even if he knew his eternal nature through spiritual revelation from the Father, as a man he would not completely understand it (this is not a new idea). And so, this theory begins with the concept that Jesus did not fully know nor understand his eternal nature, thus he was not able to explain it fully to the disciples. Perhaps this is part of why Jesus, when telling his disciples about the coming Holy Spirit, says that the "Counselor...will teach you all things..." (John 14:26).

The next supposition is that the disciples had difficulty accepting and understanding who Jesus was and why he had come - the gospel writers give us glimpses of this (in Matthew alone, 8:27; 15:10-20; 16:5-12, 21-23). They argued amongst themselves about who would be the greatest (as if Jesus was about to overthrow the Romans and restore the "Kingdom of David"), fled from Jesus during his passion, had difficulty understanding why he had died, and refused at first to believe the report of his resurrection (Mk 16:11; Lk 24:11). All of this even though Jesus had prepared them in advance (Mt 20:17-19). Did the apostles truly understand the Great Commission? Peter seems to have returned to his trade (John 21) and it appears to have been a few years before he first preaches to the Gentiles (Acts 10). Even taking the gospel to the Samaritans took quite a while and does not appear to be initiated by the apostles (Acts 8).

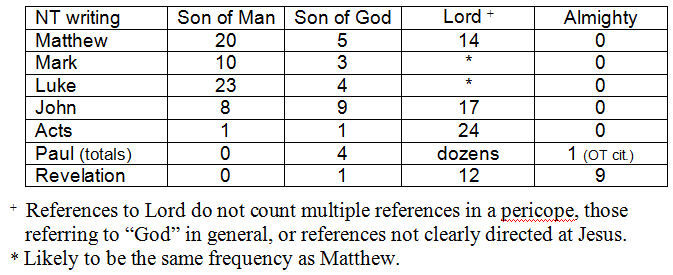

The evidence shows a progressive movement of the NT writers from Son of Man (Messiah) to ==> Son of God to ==> Lord and finally to ==> God's equivalent. The table below gives the references of the various NT writers.

First we note that the synoptic gospel writers often referred to Jesus as "Son of Man" and significantly less as "Son of God." They refer to Jesus as "Lord," but most of these references are what could be called casual as in the following: "After this the Lord appointed seventy-two others and sent them two by two..." (Lk 10:1). Based on the totality of evidence in this section, I believe these casual occurrences are closer to the kind of usage Buzzard calls for when he makes the distinction between Adonai and adoni. The formal uses of "Lord" are much different. For example, "Then the man said, 'Lord, I believe,' and he worshiped him." (John 9:38) These occurrences come much closer to references referring to deity.

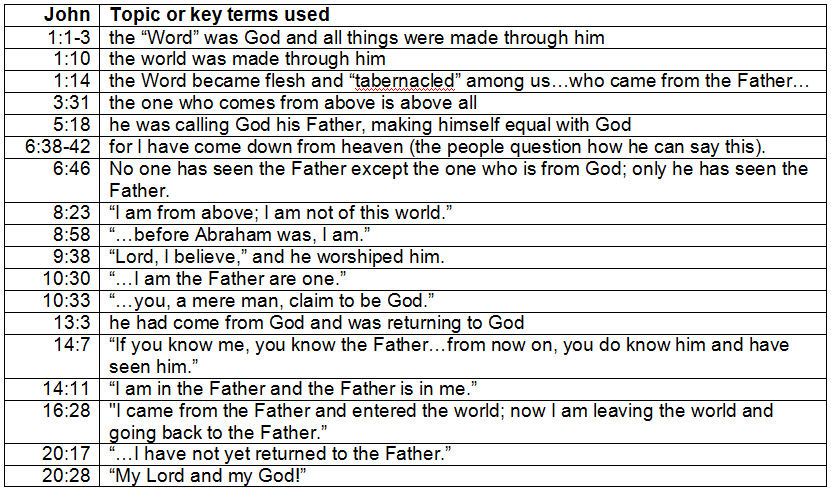

By the time of John's gospel, the difference is clear - references to "Lord" outnumber references to "Son of Man" and "Son of God" combined. This alone indicates a movement towards a clearer portrayal of deity. In addition to this, we see more direct references to the deity of Jesus and of his equality with God (see listing below).

Next we look at Luke's recording in the book of Acts. Jesus is "Son of Man" and "Son of God" only once each while he is referred to as "Lord" more than twenty times. While it is granted that many of these references to "Lord" are casual and not formal declarations of deity, it is nonetheless an important development in how Jesus is viewed. What we see is a movement from humanity to something more after the resurrection. I realize that the time gap between Luke and Acts is probably not very great, but most textual critics believe Luke is sharing/using the same source as Matthew and Mark, thus the gospels naturally reflect a pre-resurrection tone towards Jesus. After all, these are records of Jesus while he lived in the flesh. It makes sense that Acts flows more from Luke's personal experience with the risen Christ, thus the tone is post-resurrection.

Paul's writings were the first NT writings to be circulated. One can see the stark difference in the table above: Paul never refers to Jesus as "Son of Man," only calls him "Son of God" four times, but refers to him as "Lord" countless times. For Paul Jesus is not simply "Lord;" he refers most often to "the Lord Jesus Christ" - coupling "Lord" (deity) with "Jesus" (the man) and "Christ" (the Messiah title).

In the NT, kurios is a very critical reference when used for Jesus. Buzzard recognizes in a footnote (p.50n19) that kurios is a reference to God, "the LXX renders adonai, as usually, kurios." He makes this admission after he has gone to great lengths to show that "the divine title adonai, the Supreme Lord." (p.49) "It is a distinction which is clear cut and consistent. Adonai, by contrast, marks the one and only supreme God of the Bible 449 times." (p.51) In this I agree with Buzzard, and this is why Paul's use of the/our "Lord Jesus Christ" is significant. Paul uses this construction far more than any other NT writer and his intention is to reflect the triple reference cited above, deity/humanity/Messiah.

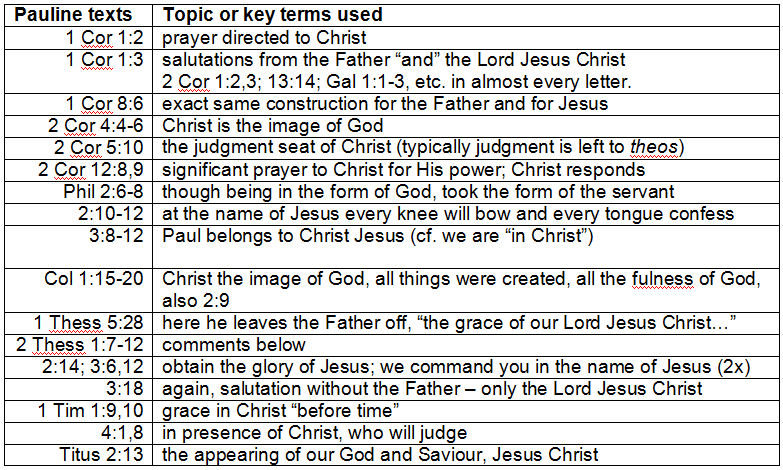

Paul also gives us some of the stronger NT references to deity:

2 Thessalonians 1:7-12

We have already seen in our discussion above (on Chapter Five - pantokrator "Almighty" in Revelation) that the coming of the Lord on the clouds in the NT always refers to the parousia (appearing) of Jesus. This text in 2 Thessalonians is one of the clear examples of Paul's teaching of the "second coming." This text revolves around "the righteous judgment of God," yet throughout the text Jesus is the subject:

- when Jesus is "revealed from heaven"

- it is Jesus who will punish them

- the presence of the Lord and his mighty power refers to Jesus due to the reference of his coming on the clouds again

- this is all to glorify the name of "our Lord Jesus."

There are far too many unknowns (author and dating) with the General Epistles, thus I am not considering them in this analysis and will skip to the Revelation.

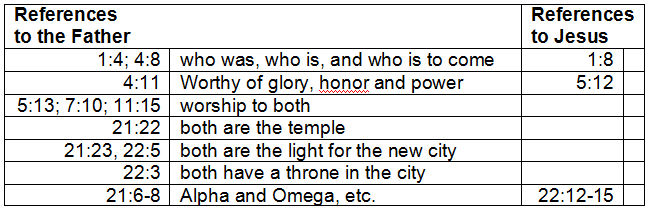

Both John and Revelation probably came to their final form in the 90's. Some doubt these two works had the same writer, but all would agree that whoever authored the Revelation was in the Johannine community. Again, as with Acts and the Pauline works, references in Revelation reflect a post-resurrection Jesus. Other than a single reference to "Son of God," Jesus is most often referred to as "Lord." As in John, Jesus is also referred to in figurative terms: the Word, the rider on a white horse, the Lamb, the Alpha and the Omega, etc. (in John he was the Word, the Good Shepherd, the Light of the World, etc.). However, there are a few significant differences that illustrate further development in the Christology of the primitive church.

The use of pantokrator ("the Almighty") in Revelation has already been mentioned in the discussion of chapter five. Here we must note how this word only appears 10 times in the NT, all but one in Revelation. The reference in 2 Corinthians is a quotation from the LXX, so the NT use of pantokrator is unique to Revelation. The writer uses pantokrator (pan-"all" and kratos-"strength, might") to indicate the omnipotent nature of the eternal God, and as was shown above (discussion of Chapter Five), also uses the word in reference to Jesus.

In addition to the use of pantokrator, the writer of Revelation points to the equality of Jesus with God the Father by assigning to him attributes used for God in the OT (1:18 - voice like waters, Ez. 43:2 and Rev. 2:8 - the first and last, Is. 44:6). The writer also uses similar, or exact language to refer to Jesus and to the Father. Many of these references have already been discussed above, thus a simple listing is sufficient here.

Summary:

The issue to be faced by the objective reader is the absence of the Trinitarian concept in the New Testament. In this discussion we have focused on the person of Jesus, not addressing the Holy Spirit at all. The issue of the Holy Spirit within the trinity is moot if we cannot see evidence of deity expressed towards Jesus. A case for the divinity of the Holy Spirit could certainly be argued via the Pauline writings, but the evidence is sparse. Most attacks on the doctrine of the trinity (as is the case with Buzzard) focus on Jesus - there is certainly plenty of evidence. What we have found is that even with Jesus the evidence for the trinity is not overwhelming.

We find a development of these concepts in the apostolic writings. Is it too much to imagine that the apostles had difficulty understanding the exact nature of the man they lived with for those short three years? These men openly reveal their lack of understanding in numerous NT pericopes:

- argument about who was the greatest in their ranks (Matt. 20:20-28; Lk 9:46-48)

- Jesus makes special effort to teach them (John 13)

- they did not understand his mission of sacrifice (Matt. 16:21-23; Lk 24:13-32)

- general lack of understanding (John 14:5, 8)

They certainly did not understand the Gentile mission. Though Jesus had given them a clear example of reaching out to Gentiles (and the "Great Commission") they had great difficulty breaking through the racial barriers. Peter must receive a dramatic vision where Jesus tells him not to call "unclean" that which Jesus has called "clean" to help him preach to the house of Cornelius (Acts 10). After this Peter must answer to the brothers for entering the house of a Gentile. This same group attacks the Gentile mission of Paul insisting that Gentiles must be circumcised (Acts 15).

If the disciples had difficulty grasping these concepts, why would we expect that they understood the complex nature of Jesus, the Messiah? In fact, it is quite clear they did not. How could we expect first century monotheistic Jews to understand that this man Jesus was, in fact, the God of the OT? Could this not be part of what Jesus meant when he told them, "I have much more to say to you, more than you can bear. But when he, the Spirit of truth, comes, he will guide you into all truth." John 16:12-13

The synoptics give us the best indication of how the disciples viewed Jesus for the first 15-20 years, referring to him primarily in terms of the Messianic and apocalyptic Son of Man as seen in Daniel 7:13-14. Paul's influence cannot be underestimated. He makes it clear that he "did not receive it [his gospel] from any man...I received it by revelation from Jesus Christ." (Gal 2:11-12) We have already seen how Paul's references to Jesus are markedly different from the synoptics. Add to this the descriptions of the eternal nature of Jesus (Phil 2:6ff; Col 1:15ff) and Paul's influence is clear. Next we have Luke's account in Acts where Jesus interacts with the disciples in prayer as one would expect with God (9:4ff; 16:7). By the time of John in the late first century the understanding of who Jesus was had developed more fully, and so had the concepts of the divinity of Jesus and the trinity.

As I mentioned at the top of this page, I continue to affirm orthodox belief in the deity of Jesus and trinitarian theology. I affirm the creeds by faith as well.

I expect to hear all manner of comments below. Your comments are welcome.

R.A. Baker

Ph.D. Ecclesiastical History

Have you ever studied the "Binitarian" view of God that many early Christians had pre-Nicea? Bill from Canada

Yes, I have read a great many of the documents pre-Nicea. If you read my book review on

Anthony Buzzard, you will see that I show how the trinity developed in Christian history. I think some of the early writers probably would not have held to a strictly trinitarian view, but would have left the Spirit out of that equation. I my paper I do not actually deal with this, but only with the deity of Jesus.

Many Christian doctrines developed over time. Some I do not agree with, others I do.

It can be tricky, but not much of this is strictly salvivic in nature. Not sure God is as worried about the details as we are...but that is just my opinion. People who study and teach theology desperately disagree with me on this.

Al B.

Thanks for responding to my email regarding the 'Binitarian' view of God in pre-nicea times. I have come to espouse the binitarian view myself after much Scriptural study and find it uplifting to know that there were early Chrisatians that believed the same.

I have no trouble accepting "Trinitarians" as sincere and genuine Christians (yet in error) but I have experienced nothing but rejection and contempt by almost all Trinitarians who view me as either a heretic or someone who needs to be saved!

The point I want to make is: I've known and walked with the Lord as a "Trinitatarian" for some 25 years and now I've continued to walk with the Lord over the last 5 years as a "Binitarian".

Its unfortunate that there needs by such acrimony over the correct understanding of the 'spirit of God' and whether or not this is a third person in the Godhead.

What is important is what [we] believe about Jesus!!

....your thoughts?....

-Bill

You are treading on ground that Christians hotly disputed in the early church.

We are taught from our youth in Christian churches that the trinity is THE orthodox position, and we are correct to teach this - the trinitarian view started taking shape in the NT and then again in early second century writers. When doctrines were finally formalized was NOT the beginning of the doctrine.

Look, I believe in the trinity, but I do have some intellectual issues with that view. You stated that what is important is what you believe about Jesus. Really? Why is Jesus important, but not the Holy Spirit?

If you say because you can find deity of Jesus in the NT texts I would answer twofold:

1. the deity of Jesus is NOT found clearly in the NT except some of Paul, John's gospel, and Revelation.

2. the NT texts were not available to ALL first century Christians.

Many Christians in China, India, Soviet Russia, etc. never had ALL the NT available to them.

Why is this important?

Because what Christians have believed through history has not always been based on the NT texts, and even now we have multiple positions based on the same texts...enough to have divided us into hundreds of denominations.

Sadly, mistreating one another is something Christians have also been guilty of throughout history. I have done it and I would guess that you have also. We are ALL guilty. We are ALL sinners in need of God's grace which He generously offers.

Interesting that Jesus did not push belief in dogma as much as we do:

Love God, love your neighbor.

Al B.

I was wondering if you would be willing to critique a short 2 page polemic I put together as Scriptural evidence against the trinity doctrine?

-Bill

I do see some problems with your position.

The main thing you are doing, which is common when someone is reading the NT text,

is to take isolated uses of a word to develop a theory, or a theology.

The problem is that the writers of the NT were not trained theologians. They did not use

all of their terms consistently 100% of the time. For example, Luke uses "the Spirit" and "the Holy Spirit" in Acts 5 and in Acts 15 (just to name two examples) as a person:

"you have lied to the Holy Spirit..."

"it seemed good to the Holy Spirit and to us..."

Now, you will probably want to say that these are references to the Spirit of Jesus or of God, but that is not what the text reads. Your presentation of "spirit" referring to the spirit of Jesus is not a good argument in my opinion due to uses like what I have just referenced.

I basically agree with you that the NT does not distinctly present the Spirit as part of the Godhead, but as I mentioned in my first response to you, early Christians had to believe without ANY NT documents (if their pastor had a few letters, most could not read anyway).

Al B.

Thanks for taking time to read and quickly critiue my polemic against the Trinity.

I have considered your comments but find it interesting that you found problems with my taking isolated uses of a word (ie. the holy Spirit) and then developing a theology from it. But isn't that exactly what the founders of Trintarianism did?

But since Scripture itself gives no clear definitive teaching on on how to understand the nature and relationship of the Father, the Son, and the holy Spirit - one is left examining all the individual 'proof texts' and tryin 'to put it all together' to arrive at some understanding of the Godhead that is consistent with all of the relevant texts. The alternative of course, is to drop all attempts at understanding and describing the Godhead which would include dropping the dogma of the Trinity.

-Bill

If you want to illustrate that the Holy Spirit is not well-defined in the NT you would do a study of ALL texts referencing the HS to see what "message" comes from those texts (Gordon Fee has a good study on this that you might want to look at)

"God's Empowering Presence: The Holy Spirit in the Letters of Paul" by Gordon Fee.

You also might want to have a look at Larry Hurtado's book, "Lord Jesus Christ."

This is mainly on the deity of Jesus, but also has some stuff on the HS.

My point: focusing on individual words is not a good methodology when dealing

with ancient writers. Many preachers use word studies - this is fine for getting a general idea of what a word means, but we must always keep in mind that most writers are not 100% consistent in word usage. The NT writers did not have copies of their letters so they could search and make sure they were using any particular term consistently.

So it is problematic whenever someone says "this or that particular word is NEVER used for...."

If you do that, you need to make sure that it is, in fact, the case.

I point you to Fee and Hurtado because they are both solid scholars, which means that they try to be objective with the data instead of just trying to "prove" their particular doctrine. Even reading the reviews of these books on Amazon might help you.

Fee is an excellent scholar. He authored the NIV Commentary on 1 Corinthians which has been hailed by many scholars as a work that has pushed Pauline/1 Corinthian studies forward.

Excellent text.

Al B.

It's ironic you should mention Larry Hurtado as he is cited in Wikipedia as describing the very early church as being "Binitarian" in its understanding of the Godhead. Here is an excerpt found under the heading "Binitarianism" from Wikipedia:

Larry W. Hurtado of University of Edinburgh uses the word binitarian to describe the position of early Christian devotion to God, which ascribes to the Son (Jesus) an exaltedness that in Judaism would be reserved for God alone, while still affirming as in Judaism that God is one, and is alone to be worshiped. He writes:

...there are a fairly consistent linkage and subordination of Jesus to God 'the Father' in these circles, evident even in the Christian texts from the latter decades of the first century that are commonly regarded as a very 'high' Christology, such as the Gospel of John and Revelation. This is why I referred to this Jesus-devotion as a "binitarian" form of monotheism: there are two distinguishable figures (God and Jesus), but they are posited in a relation to each other that seems intended to avoid the ditheism of two gods" (Lord Jesus Christ: Devotion to Jesus in Earliest Christianity, William B. Eerdmans Publishing, Grand Rapids, 2003, pp. 52-53).

Hurtado does not cite "binitarianism" as antithetical to Nicene Christianity, but rather as an indication that early Christians, before Nicea, were monotheistic (as evidenced by their singular reference to the Father as God), and yet also devoted to Jesus as pre-existent, co- eternal, the creator, embodying the power of God, by whom the Father is revealed, and in whose name alone the Father is worshiped. He writes, "The central place given to Jesus...and...their concern to avoid ditheism by reverencing Jesus rather consistently with reference to "the Father", combine to shape the proto-orthodox "binitarian" pattern of devotion. Jesus truly is reverenced as divine" (Ibid, p. 618).

Hurtado's view might be interpreted as urging that, at this stage of the development of the Church's understanding, it could be said that God is a person (the Father), and a single being; and that Jesus is distinct from the Father, was pre-existent with God, and also originating from God without becoming a being separate from him, so that he is God (the Son). This view of a binitarian pattern of devotion would posit a unity of God's being, and a singleness of the object of worship, which is sympathetic to its predecessor view in Judaism; and it also displays a plurality of simultaneous identities which is sympathetic to its successor in trinitarianism. It is a development of understanding of Christ, in other words, from which arose several understandings in the course of development, that eventually came into conflict with one another.

-Bill

I basically agree with Hurtado.

I cite him in my paper/review on Buzzard. I have not read his entire

text, LORD JESUS CHRIST, but I have worked through around the first 1/3 of it.

It is a massive work and Hurtado does go "over the top" sometimes in his details.

What I argue, which you will not agree with, is that Christianity "developed" the

theology as it went along. Jesus did not preach "theology" per se. His was a simple

message of Love God and love your neighbor. Paul, as a trained thinker, begins to push the "logical" conclusions of the various particulars he had been handed:

1. by revelation from Jesus

2. from Peter's firsthand witness (Gal 1:18 where Paul uses the greek "historia" to describe his time with Peter)

3. from other testimony he gathered along the way (Barnabas, perhaps some of the women) AND

4. from early texts that we do not have anymore (almost all scholars agree that Luke, in particular, had Aramaic written sources that he used in Luke/Acts)

Paul is the beginning of REALLY presenting Jesus as eternal and co-equal with the Father. John pushes it further in his gospel and in the Revelation (his writings are a full 30 years AFTER Paul, so he might just be reflecting what MOST Christians in his day believed). And Paul begins to develop a fuller picture of the HS.

Fee's writings have pushed scholarship on this issue.

What happens AFTER the first century is that church fathers begin to "develop" an understanding of what Paul and John were saying regarding the HS. Remember, Paul did not collect his own writings. He could not fully appreciate how faithful men after him would compile his various letters combined with all the other "sacred" writings and fit those writings into the practical workings of how the church had treated the HS in the intervening years.

Remember that it is not ONLY the NT documents that were used by the early church - the Didache, the letter of Barnabas, Shepherd of Hermas and other texts - all were read and treated as "inspired" by many early fathers. Also, the Christian churches from around 70 to 120 AD continued to grow and develop their thinking/doctrine without having ALL the NT documents in hand.

ALL of this went into the development of what would later be called the "trinity."

All "Bible believing" people like to say that we can ONLY hold onto what the NT teaches, but when we say this we fail to realize that the early Christians did NOT do this - indeed, they could NOT do this because they did not have ALL the NT documents neatly in hand. They could not point to chapter and verse - this did not exist. They could not even point to "page thus and so." One pastors copy of Paul's letter to the Thessalonians might actually contain both letters plus the letter the church wrote back to Paul while the next pastor might only have what we know as the first 3 chapters which end with a "conclusion."

Some conservative scholars might argue, "Yes, but the early churches and pastors had the apostle's traditions (paradosis) handed down to them." While this is true, we can see in the various extra-biblical writings of the first few centuries that this paradosis was not consistent from region to region. Different regions held to different traditions and indeed to different "sacred" writings.

"But what then should we believe?"

Well, I do not fully know the answer to this question. I state very clearly regarding the topic that started our conversation (the trinity) and that I believe in the orthodox doctrine of the trinity even though I do not see it clearly spelled out in the NT. I believe it even though I have some intellectual/logical problems with it. But I have also clearly written about my disagreement with the doctrines presented by most conservatives and evangelicals that our faith is based on the NT texts and ONLY on what those texts teach. I do attempt to base my beliefs on the NT teachings, but I also accept that the NT is not 100% consistent from subject to subject. This makes it a bit more difficult, but I believe this is exactly how Christianity has always had to operate. Our belief system is more dynamic than this as is evidenced by the fact that NOBODY believes EXACTLY the same things as the next person on EVERYTHING.

This is why we have so many denominations and schisms.

This is also why I stated in an earlier communication that I am..."Not sure God is as worried about the details as we are...but that is just my opinion."

I will leave you with a few of my favorite quotes. I think we both would do better if we could abide by these:

Now we see through a mirror darkly (Greek - "in enigma"), then we shall see face to face. -

St. Paul, 1 Cor 13:12

Our vision is often more obstructed by what we think we know than by our lack of knowledge.

- Krister Stendahl, Paul Among Jews and Gentiles

Truth, though truly absolute, seems to change as we change. Yet we must accept the Truth as we see it. - J.S.Gibson III

The World is Change, Life is Understanding.

- Marcus Aurelius, Meditations

Al B.

My pursuit of God often digresses into a pursuit of knowledge & understanding, but your articles help remind me why i asked the questions to begin with.

There are things about God/Christianity I don't understand, so i go searching for the answers. Sometimes my questions are answered, but what i usually find is just more information i hadn't considered, which leads to more questions, which eventually leads to despair when i can't seem to wrap my brain around the thing that i am now convinced is REALLY important to my faith. This is usually because somewhere along the line my motive changed from seeking God to seeking knowledge, and i just get hung up on having it all figured out. The concept of the Trinity is an example of something my mind gets stuck on, and i start thinking about God like an equation that needs to be solved.

But the articles on your website don't seem to perpetuate this downward spiral into logical oblivion. I am given helpful information backed by scholarly research, but more than that, i am left with the good feeling that God is bigger than all my unanswered questions, and that the burden of figuring out the secrets of the universe isn't mine to bear. The historical aspect of your articles plays a large role in this. Being reminded that the 1st century church, and even the apostles themselves, did not fully comprehend the God they served is something i need to hear routinely.

So... in conclusion... your articles "help remind me why i asked the questions to begin with" by shifting my focus from a purely intellectual study of God to the broader scope of God's involvement in history. You remind me that God has feet, and he's not just an apparition that lives in our thoughts. And when God has feet, i have something real to pursue, and i am ultimately reminded of my own conversion and the experiences that made me want to pursue the living God in the first place.

Derek S., Nashville

THIS is a great comment! So many things in this comment that I think are highly valuable for thinking Christians, those willing to question and wrestle with the subtleties and difficulties of faith.

I really like your comment, "The concept of the Trinity is an example of something my mind gets stuck on, and i start thinking about God like an equation that needs to be solved."

This is more common than some might think. Type A people who also tend to be Left-Brain oriented, can easily find themselves struggling to "figure things out" in the Christian or spiritual realm. I am in this camp and I must confess that for years I strained and struggled to "solve" the equations!

While I believe that using the mind honors God ("Thou shalt love the Lord thy God with all of thy heart, soul, mind and strength"), and that the Christian faith can handle logical scutiny and critical thinking, I also believe that there are many aspects of faith that cannot be explained or understood fully. Because of this, there are aspects of faith that we must be willing to accept as mystery and/or just beyond explanation. God is NOT an equation that we must solve.

This can be offensive to the highly intelligent until such a person is willing to admit that many things in life are this way. Can you fully explain and understand the love you feel for your children? How can you explain Love? What about the nature of a universe that is expanding and contracting at the same time? (if this continues to be the prevailing opinion amongst physicists) Even the bending of the space/time continuum that is currently being pursued, ways of better understanding Einstein's Theory of Relativity.

The axiom learned by many of us in school, "the more you know, the more you realize that you do not know" is true. Thus those who have great amounts of knowledge should also have the most humility because they should realize how much they do NOT know. I realize there is a difference between knowledge not yet gained and the concept that some knowledge is not discernible. These are similar, at least in my mind. Scientists 300 years ago would have known nothing about space travel. It would have been unknown to them. Yet, it would later become fairly common knowledge. I think great minded people should understand the limits of their knowledge and understanding.

Questions, Comments or Criticisms:

You can send an email to directly to me Al Baker, CH101.

CH101 retains the right to edit and post comments/questions unless you specifically ask that your comments NOT be posted. Comments that are personal or private are never posted...only questions about Church History, the Bible, etc.